Crew Profile: Fireman / Stoker Barrett

Frederick William Barrett had worked on ships for about 10 years by the time he signed onto Titanic. Born in Bootle, England, Frederick joined the hundreds of crew who registered into service on Titanic on April 6, 1912. On the ship, he was a leading fireman, as he had been on the American Line steamship City of New York. His role meant he had additional responsibilities compared to his counterparts, like overseeing a boiler room and firemen, as well as completing special tasks.

Frederick was on duty in Boiler Room 6 when Titanic collided with the iceberg on April 14. He called to shut the furnace dampers when the bell sounded and red lights flashed. Ice-cold seawater began pouring into the starboard side of the Ship. His decision to shut the dampers ensured water wouldn’t immediately hit the fired boilers.

As the watertight doors lowered and shut, Frederick made his escape into Boiler Room 5. He then climbed a ladder over the bulkhead to Boiler Room 6, where he noticed the intruding water was already 8 feet deep. A small opening in Boiler Room 5 meant water was slowly coming into it, too. The engineers on duty were trying to work the pumps to remove the incoming seawater. Frederick stayed at his post and gathered a group of 15 to 20 firemen to make sure no water was in the boilers and keep the fires lit before sending them up.

Frederick stayed with engineers Jonathan Shepard, Bertie Wilson, and Herbert Harvey. During that time, Jonathan broke his leg, and Herbert and Frederick carried him to the pump room to tend to his injury. Suddenly, water rushed into Boiler Room 6, and Frederick was ordered to make his way up. He never saw those men again.

Frederick made it to the upper decks and into Lifeboat 13, along with passengers Dr. Henry Washington Dodge, Lawrence Beesley, and Mrs. Agnes Sandström and her two children. Just as his lifeboat was lowered to the water, it drifted directly below Lifeboat 15, which was lowered less than a minute later. Heroically, Frederick sprung over those seated, cut the ropes, and pushed the boat away. He then took charge of the lifeboat until it had cleared the immediate danger.

Frederick testified in both the U.S. and British Inquiries and shared his remarkable story. He continued working as a fireman at sea for over a decade until he took a job on land as a timber laborer. He died in 1931 at the age of 48 from pulmonary tuberculosis.

Frederick Barrett’s work below decks was vital to the entire operations of Titanic’s maiden voyage. His sweat and manual labor ensured her boilers were lit, steam energy was produced, and the reciprocating engines ran. His quick thinking and bravery led to power remaining on and the rescue of many passengers and crew, including avoiding danger in his very own lifeboat.

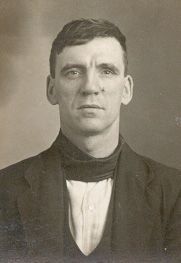

Frederick Barrett (undated). Public domain

This article from the Surrey Times and County Express newspaper in May 1912 relates that Frederick Barrett would testify in the British Titanic inquiry.

Crew Profile: Fireman James Crimmins

ames Crimmins was 21 and had been working on board oceanliners for a couple of years by the time he signed on to Titanic in Southampton, England, on April 6, 1912. Continuing his role from his previous ship, Oceanic, he joined as one of the several hundred firemen to work amongst the noise, ash, and heat in the belly of the Ship. One of his co-workers was his brother-in-law, Tommy Kerr.

James’ role as a fireman meant he spent hours shoveling heavy mounds of coal into one of 29 boilers. Soot and ash bellowed as trimmers dumped coal at his feet and, following the timed rotations, kept his furnace at the proper heat to create enough steam to power the great Ship. James would listen for the stoking indicator’s loud gong and follow the displayed number to know which furnace to fuel and for how long. So long as Titanic needed power, firemen were on the job.

On the night of April 14, 1912, James was working in one of the boiler rooms at the base of the Ship. Suddenly, he felt a bump that knocked him to his feet. Titanic’s boiler rooms began flashing red lights and closing their watertight doors. The massive iceberg opened Titanic’s starboard side to the cold ocean at 11:40 p.m. However, no one in his boiler room knew what had happened. He continued firing his furnace, following the order to stay at his post. His work kept Titanic powered. James was later ordered to shut his damper and escape to the upper decks.

Navigating through Titanic’s inner crew passageways, he found himself on the aft starboard Boat Deck. James then saw the severity of the situation: Titanic was sinking fast. Noticing the panic and great need for help, he began assisting those around him into the lifeboats. Since he was on the starboard side, James followed the command of First Officer William Murdoch to load women and children first and then men. Soon, all available women and children were in a lifeboat, so the men started filling empty seats. James helped row away from the sinking vessel and waited with hope to be rescued. Like his colleagues, James wore only his boiler room clothes, light garments ideal for the furnace’s intense heat but not nearly warm enough for the below-freezing conditions.

It wasn’t until he was on board the rescue ship Carpathia that he realized his brother-in-law Tommy did not make it. Fewer than 50 firemen survived that night. Only a handful of those on duty survived the tragedy.

James passed away in 1956 at the age of 65 in Southampton.