Helen Churchill Candee’s Story of Bravery and Brilliance

Helen Churchill Candee, born into an affluent New York family in 1858, was a writer, journalist, political correspondent, interior decorator, feminist, and Titanic survivor who defied restrictive gender norms to forge her own independent career and life. After the end of her abusive marriage in 1895, she supported herself and her children through writing—a rarity for women at the time. Her bestseller 1900 book, How Women May Earn a Living, was a groundbreaking guide for women seeking financial and social independence. She wrote extensively on art, architecture, travel, and women’s issues, becoming a respected voice in progressive circles.

By 1912, Helen was an established journalist and socialite living in Washington, D.C. The 53-year-old moved in influential diplomatic circles, including dignitaries, royalty, and government officials. Her self-taught expertise in decorative arts led her to become one of the first professional interior decorators. Helen spent time in Europe studying architecture and design, and her book Decorative Styles and Periods solidified her reputation. Her work included the 1909 expansion of the West Wing of the White House for President William Howard Taft.

As a feminist and intellectual, Helen embodied the changing role of women in the early 20th century. She publicly supported the National Women Suffrage Association and participated in marches, including the historic Washington, D.C. Woman Suffrage Procession in 1913.

Portrait of Helen Churchill Candee. Public domain

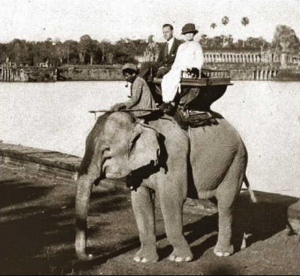

Helen Churchill Candee, her son Harry, their guide, and the elephant Effie in Angkor Wat, Cambodia, in 1922. Helen was considered an expert in the history and culture of the Far East. Public domain

Research for a book led Helen to France by April 1912, where she boarded Titanic at Cherbourg as a first-class passenger. She was returning to the United States after receiving news that her son had been injured. Helen had friends already on board, D.C. denizens Maj. Archibald Butt and Francis Millet. She quickly became acquainted with other first-class passengers, including Edward Kent and Hugh Woolner.

When Titanic struck the iceberg on April 14, Hugh assisted Helen into a lifejacket and up to the Boat Deck. Along the way, the pair ran into Edward, whom she entrusted with a flask and a small ivory cameo believed to be of her mother. Tragically, Edward perished in the sinking. The cameo and flask were later recovered from his body.

Helen boarded Lifeboat Six, the same boat occupied by Margaret Brown. However, due to the listing of the Ship, she fractured her ankle upon jumping into the partially lowered boat. Despite the pain, Helen took an oar and rowed with the others.

After being rescued by Carpathia, Helen recovered in New York and continued her writing career. She published the first in-depth eyewitness account in a major magazine, which also became her last on the subject. Her piece, “Sealed Orders,” was published just weeks after the sinking in Collier’s Weekly, accompanied by photographs taken from Carpathia showing Titanic survivors.

Helen’s survival only strengthened her resolve to live an independent and adventurous life. She went on to serve as part of the Red Cross and become one of the first female war correspondents during World War I, even helping in the recovery of a young Ernest Hemingway. Later, she traveled extensively in Asia, writing and producing several of the earliest Western studies of Asian culture and architecture. She was celebrated for her work at a native ceremony by the King of Cambodia, and she eventually became a lecturer on the Far East. She also wrote for National Geographic.

Helen’s trailblazing days finally came to an end in 1949 at the age of 90. She embodied the changing role of women in the early 20th century as a self-made woman. Through her work, she challenged conventions and advocated for financial independence, artistic appreciation, and intellectual pursuit at a time when women were often expected to remain in domestic spaces.

Helen advocated for women’s suffrage. She is seen at center atop a horse at the March 3, 1913, Woman Suffrage Procession in Washington, D.C. Public domain